Written by Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

| May 30, 2024

➡️ Video Lesson ➡️ Introduction

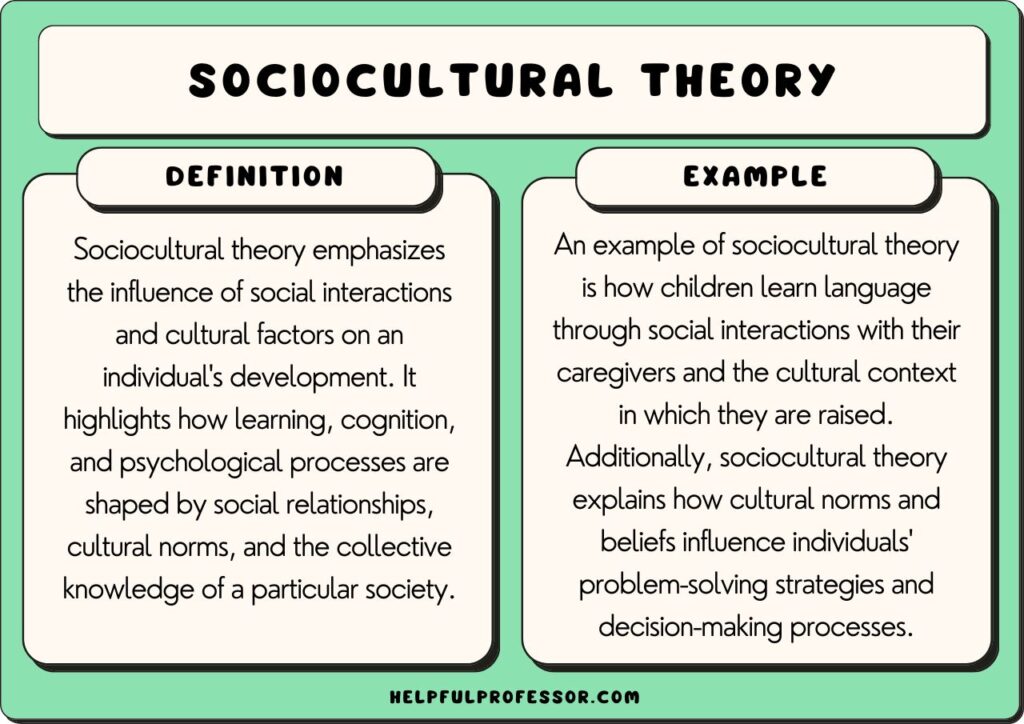

Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory of learning explains that learning occurs during social interactions between individuals. It is one of the dominant theories of education today. It believes learning happens first through social interaction and second through individual internalization of social behaviors.

In the sociocultural theory, students and teachers form relationships in the classroom to help the student learn. The relationships help facilitate social interaction and active participation in the learning tasks. Students learn through observation, listening and talking through their tasks.

Contents showSociocultural theory, also known as social constructivism or socioculturalism, is defined by educational scholars as:

Don’t forget to paraphrase the definition to show your marker that you have a good understanding of the theory. Then, reference these sources at the end of the sentence. For example, if I were to paraphrase the definitions above, I’d say it something like:

Sociocultural theorists believe that learning happens as a result of social interactions and takes place within a specific cultural environment (Bates, 2019; Leonard, 2002; Nagel, 2012).

This is the most important concept in the sociocultural theory of education: we learn through social interactions. This concept differentiates itself significantly from the ‘cognitive-constructivist’ ideas of Piaget. Piaget saw children as ‘lone scientists’ who learn by exploring their environment and absorbing information. By contrast, sociocultural theorists (like Lev Vygotsky) see learning as fundamentally shaped through interactions between children and the adults in their environment. This starts from early childhood and keeps going – right up to adulthood! In other words

In other words, there is a bigger role of the teacher or parent in sociocultural theory than perhaps any other educational theory.

Above I told you that sociocultural theorists think that learning is influenced by social interactions.

The logical extension of this belief is that children learn differently depending on their social environments.

Let’s compare a child learning in a traditional Indigenous Australian culture vs. in a contemporary Western classroom.

In the traditional Indigenous Australian culture, children aren’t sitting in a classroom – no way! They’re off learning on the job. The sons are learning to hunt kangaroo with their fathers while the daughters are off learning to hunt turtles with their mothers.

In the contemporary Western classroom, children are sitting in classrooms learning to read books day in, day out.

How might these children’s learning differ?

The traditional Indigenous children will probably be fantastic at throwing spears and spotting animal footprints in the soil. They might be very good at walking silently to get close to animals, and they may even be very good at creating clothing out of animal skins.

The contemporary Western children will probably be very good at reading books and standing patiently in line-ups before entering the classroom. But if they end up out in the Australian outback on their own? They’ll probably starve.

This means that Piaget’s universal stages of children’s cognitive development may be a bit wrong. Children may development very, very differently around the world!

Three key theorists in the development of sociocultural theory are: Vygotsky, Bruner and Rogoff.

The most well-known sociocultural theorist, Vygotsky developed many key terms like ‘Zone of Proximal Development’ and ‘More Knowledgeable Other’ (see below). He wrote the influential text Thinking and speech (1934) (also published as ‘Thought and Language’) and had a collection of his other works published under the title Mind in Society in 1978. Despite his scholarly work taking place in 1920s and 30s Russia, his ideas only gained popularity in the West in the 1980s.

Following the lead of Vygotsky, Bruner continued to prosecute the argument that language shapes thought. He worked in Harvard and Oxford Universities and wrote extensively on the role of the parent and teacher in influencing language. He videotaped interactions between parents and children to examine how children imitate and internalize their parents’ language. In 1983 he wrote Child’s talk: Learning to Use Language. His most influential contribution today remains the concept of ‘scaffolding’, discussed below. Bruner also coined the famous spiral curriculum concept.

Barbara Rogoff is one of the most influential female developmental psychologists of all time, representing a break from the all-male establishment that resulted from gender bias in the academies of the 20 th She completed a PhD exploring language development amongst the Tz’utujil Mayan people of Guatemala. Through her works, she reinforced the idea that language develops in unique cultural contexts. Her key contributions to sociocultural theory include the terms ‘cognitive apprenticeships’ and ‘guided participation’, discussed below.

Like all theories, sociocultural theory has many positive and negative aspects. The theory has blindspots and limitations which you need to know about in order to minimize any harmful effects in the classroom.

But, on balance, it also has some amazingly useful elements that you should use regularly in your teaching.

So, let’s take a look at the key benefits and limitations of the sociocultural theory for teachers.

Sociocultural theory is one of the most useful theories for education. Most of us use it every day in classrooms!

Here are a few of the benefits of the theory for educators and learners:

Teachers also need to be aware of the many limitations of sociocultural theory. Why? Well, because we should realize that different theories are needed in different circumstances.

Social learning isn’t ideal in all situations!

So, here are some limitations that seem to be inherent in this theory:

Here are four common examples of sociocultural theory in classrooms:

Can you think of more applications of sociocultural theory? Add them to the comments below and I’ll add them to the official list in the post!

One of the most important terms in the sociocultural theory is ‘internalization’. It’s a term Vygotsky used to explain how we learn.

It is really quite a simple concept: we internalize the knowledge that we observe, see and interact with. The more we’re exposed to a certain way of thinking, the more we internalize those thought patterns.

This is different to Piaget’s view, because Piaget didn’t say much about how we were influenced by others. He didn’t think we internalized others’ ideas. Rather, he thought we came up with ideas all by ourselves.

Let me break this difference down again:

This makes sense, when you think about it. If you’re born into a Christian family, you’re more likely to come to believe in Jesus than if you aren’t. If you’re born into an atheist family, you’re more likely to internalize atheist ideas and grow up atheist, etc.

➡️ 2. Active Learners Co-Construct Knowledge

Sociocultural theorists believe learners can influence each other.

So, I’m not just going to passively internalize and absorb the knowledge around me. I’m going to mull it over, think about it, and propose new ideas.

I might share those new thoughts and ideas with the people around me and they might think “Yeah, you’ve made a really good point. I’ll change my thinking a little based on your point, too.”

There’s two important things I’ve just highlighted here:

One of Vygotsky’s key ideas is that language helps us learn.

Again, this is in clear contrast to Piaget’s idea that language is merely the expression of our learning.

Here’s a few examples of how we use language as a tool for our own learning:

The next point expands on this by highlighting one of Vygotsky’s key arguments: that as our language skills get more complex, we internalize our language.

➡️ 4. Private Speech

To Vygotsky, language is so integral to learning that we may not be very good at thinking anything in much detail, really, if we don’t have command over language.

Vygotsky observed that children often speak out loud when thinking. They might just blurt out their thoughts as a matter of course. Next time you’re watching a 2 or 3-year-old, observe how they might randomly start saying things: “Duck!”, “Look there!”, “Water!” as they go about their lives.

As we get older, we manage the skill of internalizing our language. This is probably most evident in reading. We being by reading out loud before mumbling the words and then, eventually, reading in silence.

Here, Vygotsky believes that language hasn’t disappeared – language remains central to our thinking – but it has become private speech.

Interestingly, as I’m learning Spanish, I’ve become very conscious of this. I realize that I still think in English and have to translate my thoughts into Spanish. Hopefully one day I will master the mental tools of the Spanish language and learn to think in Spanish, too.

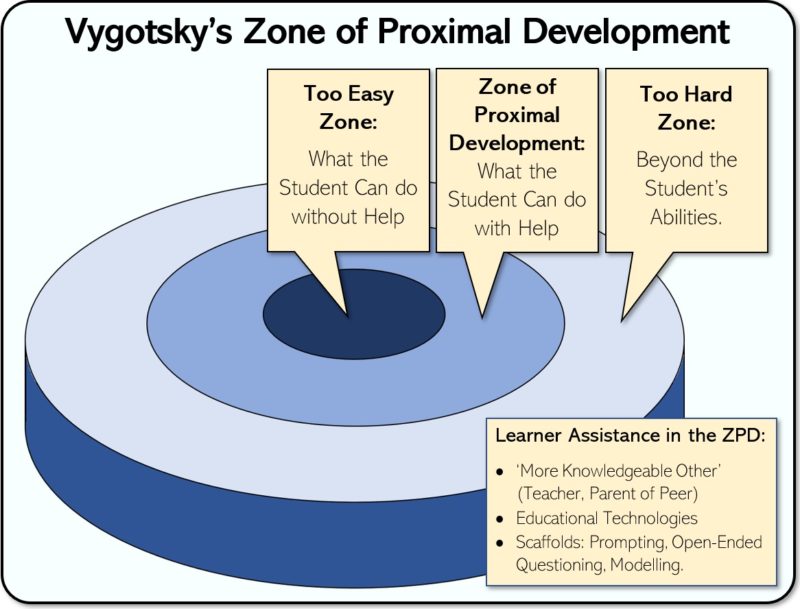

➡️ 5. The Zone of Proximal Development

This idea is great for teachers. It shows us where we need to focus our teaching. It’s our job to provide tasks that fit right inside a student’s ZPD.

To do this, we need to know our students very well. We need to conduct pre-tests of their prior knowledge to figure out what they need to know next: something that we think is within their grasp if only we give them a little help along the way.

➡️ 6. Pretend Play

Play. Play as a child. Play as an adult. Play, explore, and play some more.

Well, according to Vygotsky, when we play we often work right within that zone of proximal development.

Think about a child playing: they might mimic their parents answering phone calls, sweeping the floor or putting on lipstick.

When they’re doing these play tasks, these children are practicing new tasks that are just beyond their grasp: they can’t really answer a phone call. But we might play with them and say: “Pick up the phone” and they’ll hold the phone to their ear and say “Hello!” and we’ll clap and laugh with them.

By playing, the child is practicing those just-too-hard tasks.

Even as adults we do this regularly. I might use a game simulation to practice how it feels to fly a plane before giving it a go myself. I might use 3D computer design software to see whether my ideas for my kitchen renovation will work out properly.

Or, I might practice playing baseball with my friends before the game on the weekend. Here, I’m using fun and low-risk play-like activities to prepare myself for ‘the big game’ when I have to perform those tasks that are just a little hard right now!

Related:

Any student of sociocultural theories of education needs to know this term.

Vygotsky developed the term ‘more knowledgeable other’ to explain how learning occurs through social interaction.

He thought that the best sorts of social influences for students’ learning are people who are … well, more knowledgeable than us!

For our students, we are their more knowledgeable other. For children, their first and most important more knowledgeable other is their parents.

Other more knowledgeable others might be peers: older siblings or friends who are just a little bit smarter than us.

A more knowledgeable other is a really great positive influence because they can help us more into our ZPD. If we’re working with someone not as smart as us, they might not be as good for our learning. They can’t extend us quite as much as our more knowledgeable other.

A good idea for teachers is to pair lower level students up with the top students so the top student can influence the lower-level student and help them move through the zone of proximal development.

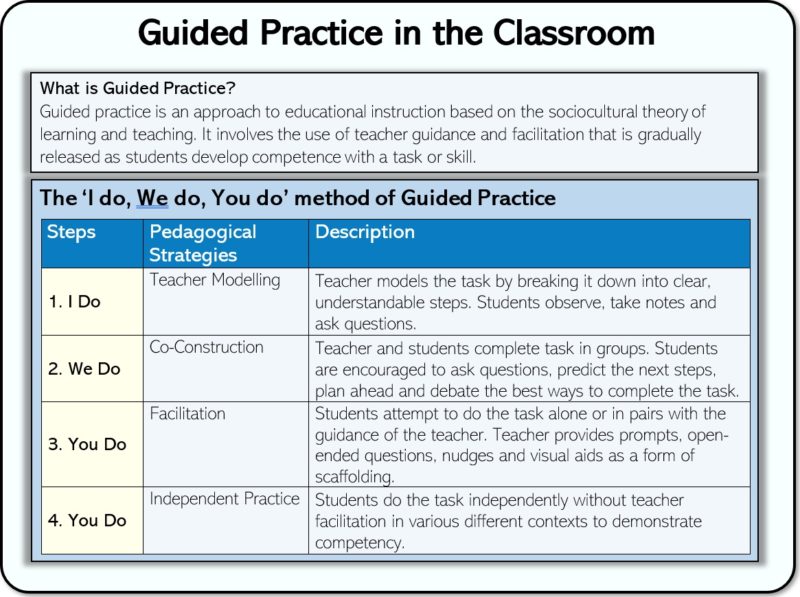

A good more knowledgeable other will slowly release control of the learning from the teacher to the student. They might start by modelling information, then doing the task as a pair, then facilitating the learner while they do the task alone. This is often called guided practice or the I Do, We Do, You Do method:

➡️ 8. Scaffolding

This term is usually attributed to Vygotsky. But that’s a myth. The person who came up with the term ‘Scaffolding’ is Bruner.

When we think of instructional scaffolding we usually think of those ugly structures that builders put up around buildings during construction.

The point of scaffolds is to help build the building. They’re there when the building is being built to help hold it up and make it easy for builders to construct it.

But, when the building can stand on its own and is ready for the world … builders take the scaffolding away!

In just the same way, instructional scaffolds can be used for students.

Scaffolding for learning is all about helping children learn concepts that are just too hard to do on their own.

In other words, scaffolding is what we do to help children move through their ZPD.

Some ways we can scaffold learning include:

Can you think of any more ways you scaffold learning? Provide your ideas in the comments section at the end of this article!

➡️ 9. Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory

One theoretical idea that very closely aligns with the social constructivist approach is Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory.

According to Bronfenbrenner, learning is influenced in four different socio-historical spheres: the micro, meso, macro and chronosystems. Let’s take a look at each:

I could delve very deep into this theory, but that’s for a whole different article! If you want to learn more about Bronfenbrenner, try out this post from the Mental Help website.

➡️ 10. Bandura’s Social Learning Theory

Another theorist who is very closely connected to the sociocultural approach to teaching and learning is Albert Bandura.

Bandura believes that learning essentially happens through observation. By observing others, we can learn.

Bandura uses Vygotsky’s ideas of the importance of private speech for learning, but calls it ‘self-talk’. He sees learning happening through three processes:

Bandura’s work is perhaps best represented through the bobo doll experiment, which is shown in the video above.

According to this experiment, children saw adults’ physically aggressive actions towards dolls, and then later tended to repeat those aggressive actions against the doll. Here, we can see children learn and imitate the actions of people around them.

The two terms ‘cognitive apprenticeships’ and ‘situated learning’ are basically the same terms.

Lave and Wenger are two of the most influential theorists for this discussion.

To give you a fly-by of these ideas: they mean that learning appears to happen really quite well when people are paired up with ‘experts’ in a craft.

The most obvious version of this is trade apprenticeships. A young person – maybe 18 years old – might start a plumbing apprenticeship.

How do you think they’ll learn?

Well, they’ll follow an experienced plumber around and learn from him as he does his craft. A pipe breaks: and the apprentice watches and learns as he watches the expert fix it. Two pipes of different sizes need to be connected: the apprentice observes again to learn how to manage this situation.

When multiple people come together to work on a craft, they’re called a ‘community of practice’. When a young person joins that community of practice and learns-by-doing, what happens? They learn from the experts!

➡️ 12. Guided Participation

Look, I’m a huge fan of Barbara Rogoff.

Like, really … she based her PhD on learning within Guatemalan Mayan cultures. She is THAT cool!

Okay … back to business.

Rogoff uses the sociocultural idea of cognitive apprenticeships (see above) and applies it across cultures.

She sees cognitive apprenticeships as a form of learning that seems very natural in non-Western cultures. This goes for the Mayan culture she studied in Guatemala, but also many Australian Indigenous cultures, too. I’m sure it’s common in many Indigenous cultures around the world.

By contrast, we in the West seem to separate the adults doing things with the children learning things.

I mean, think about it: we literally send the adults off to work and the children off to school. We place them in classrooms with four walls and teach them through direct instruction rather than guided participation.

Why shouldn’t children learn by participating in life? Why shouldn’t they go to work with the adults and learn how to do the tasks the adults do?

Well, I probably just opened a huge series of new thoughts in your mind about the pros and cons of each approach.

But hey, I want you to think and learn and come to your own conclusion and … most importantly … find this stuff interesting enough that you think about it in your car on the way to work tomorrow.

So you can decide on the merits of the Mayan approach vs. the Western approach tomorrow in your car!

➡️ 13. Distributed Cognition

Distributed cognition is a concept from sociocultural theory that explains how, if learning is social, then we can share our thinking!

Distributed cognition is defined by Busby (2001, p. 238) as:

“Solving problems by collaboration, where none of the collaborators individually can have a full appreciation of the problem”

Think about it this way: a task is too hard for one person to do. There are just too many moving parts.

But, what if you got four people together and shared the task? Could you complete the task now? Maybe different people in the team have different packets of knowledge, and together the task can be achieved.

Distributed cognition also works with computers. You might use a calculator or excel worksheet to help you to complete a task.

This means that you can offload all of the big data analytical tasks to the computer and focus on the higher-order thinking tasks like problem solving and making strategic decisions.

Here, then, social learning is becoming not just about people interacting with other people. Now, computers can have a social impact on our learning, too!

Bates, B. (2019). Learning theories simplified. London: SAGE.

Duchesne, S., McMaugh, A., Bochner, S., & Krause, K. L. (2013). Educational psychology: for learning and teaching (4th ed.). South Melbourne, VIC: Cengage Learning.

Gray, C., & MacBlain, S. (2015). Learning theories in childhood. London: Sage.

Leonard, D. (2002). Learning Theories, A to Z. Connecticut: Greenwood Press.

Nagel, M. (2012). Student learning. In R. Churchill, P. Ferguson, S. Godinho, N. Johnson, & A. Keddie. (Eds.). Teaching making a difference (Vol. 2, pp. 74-88). Milton, QLD: Wiley Publishing.

Neaum, S. (2010). Child development for early childhood studies. London: SAGE.

Pritchard, A. (2008). Ways of learning: learning theories and learning styles in the classroom. London: Routledge.

Schunk, D. H. (2012). Learning theories an educational perspective sixth edition. London: Pearson.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1986). Thought and language (A. Kozulin, trans.). Cambridge MA: MIT Press.